We live in an inflationary era that was established shortly before the great war of 1914 to 1918. Bring up a 100 year gold chart measured in any western currency, and we can see the effect of this. Every single currency has lost about 99% of its purchasing power over that time period. In the case of the Norwegian Krone (NOK), there's been a fall of more than 99% just in my lifetime. I remember buying a sweet treat for myself for 0.02 NOK as a kid. Today, 50 years later, 2 NOK buys nothing at all.

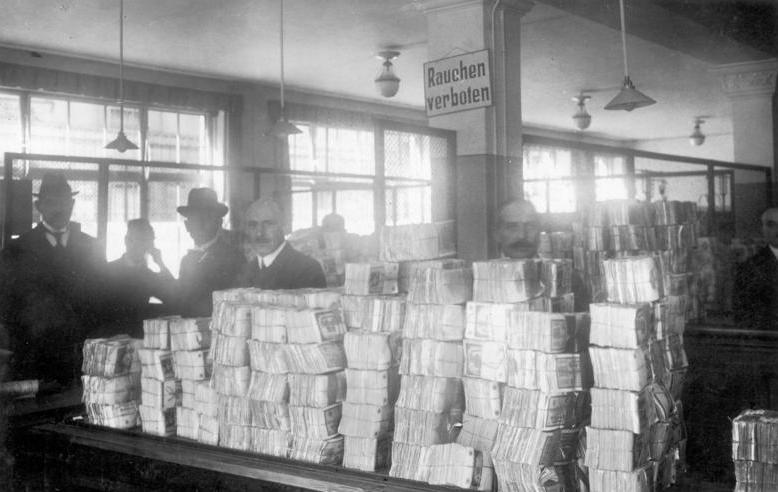

The erosion of purchasing power has been remarkably well managed over the past 100 years. Inflation has been tolerable in all but a few counties, with the collapse of the German Mark during the Weimar republic as the most notable example of how inflation can suddenly get out of hand.

This raises the question as to what the Germans did differently from other western nations to end up with hyperinflation. Also, what signs, if any, were there of an imminent collapse? What were the right and the wrong moves? What can we learn from the Weimar republic?

Luckily for us, there's no lack of history books on the subject. I just read Jens O. Parsson analysis, a 15 page introduction to his book about inflation in America, which I found quite enlightening. Not least because it mentioned a number of things that are currently being repeated all over the world, and in the US in particular.

First thing to note is that Weimar Germany didn't do things all that differently from other countries. Their mistake was merely that they went too far. Second, there was a persistent delay between the monetary debasement and its effect on the economy. What was visible were the effects of earlier decisions. The collapse from 1922 to 1923 was a result of bad decisions made in 1920 to 1921, which in turn were based on the decision to finance the war of 1914 to 1918 through deficit spending.

The delay between monetary inflation and price inflation meant that current prices didn't fully reflect the debasement. This effect worked to the state's advantage since they were first in line to spend the freshly printed money. As a consequence, there was little political will to stop. There was no opposition to deficit spending. Furthermore, monetary inflation sustained a financial boom that gave the economy a veneer of health. Politicians could point to new all time highs in the stock marked as a sign of strength. But outside the financial markets there were signs of decay everywhere.

The quality of German industrial production deteriorated noticeably. Things that used to work fine started to fall apart. In society at large, speculators got richer while just about everybody else got poorer. A class of conspicuous super rich speculators emerged. While some were in awe of these clever ones who were able to game the system so perfectly, others resented them for their smug disregard for sound business practices. Businesses didn't have to make money, and they didn't have to make sense. All sorts of Mickey Mouse companies popped up, mostly centred around financial services. There were legions of nonsensical paper shuffling jobs. There were also huge conglomerates of companies with little to no synergies between them. Leveraged to their eyeballs, these companies invested heavily in all the latest and greatest in technology.

Instead of dealing with the heart of the problem, politicians focused on rules and regulations, hoping in that way to reign in the consequences of their own irresponsible monetary policies. There was rent control, preventing landlords from raising rents in response to inflationary pressures. There were minimum wage laws and limits to legal working hours. Huge inefficiencies of commerce arose as a consequence.

This went on until there was a stock market crash, followed by hyperinflation. This crash pulled the valuation of all industries down by about 25%. Good quality companies went down just as much as the Mickey Mouse ones. When hyperinflation kicked in, stocks remained at their low level in German Marks, but relative to foreign currencies and gold, the fall continued until the money printing stopped cold turkey in 1923.

The sudden stop in credit expansion killed off all the Mickey Mouse companies. Only top quality companies survived, and they were dirt cheap. The total price of the Mercedes motor company was about 300 cars of their own brand. Anyone who flipped their gold for an index fund of good quality German companies back then would have made an absolute fortune.

Reading Parsson's analysis, I couldn't help feeling we're currently living through times similar to Weimar Germany 1921. Time will tell if we'll see 1922 and 1923 as well, but if we do, I'm confident I'm correctly positioned for the turmoil to come.

|

| Paper money |

No comments:

Post a Comment