Three years have passed since NASA’s DART probe hit the asteroid Dimorphos. An impact that shortened its orbit around its parent asteroid Didymos by ten minutes.

Successful mission

The result was well within what NASA had predicted, and was therefore considered proof of concept for the kinetic impactor method. However, a study of debris ejected by the impactor shows that large fragments are moving faster than expected.

Something is a little off relative to their theory.

Erroneous predictions

On the other hand, I made two predictions that have not come true. One about the composition of the asteroid, and another one about its change of orbit.

I was also under the misapprehension that the goal of the impact was to widen the orbit. But my prediction had to do with changes to the orbit, independent of whether they are made wider or shorter. So, this is not a big deal.

My main point was that the orbit would be less impacted than predicted by NASA, and that the orbit might even be partially or fully restored to its original after a few years.

This didn't happen. But the reason for this may be found in the unaccounted for energy observed by NASA.

Stability of orbits

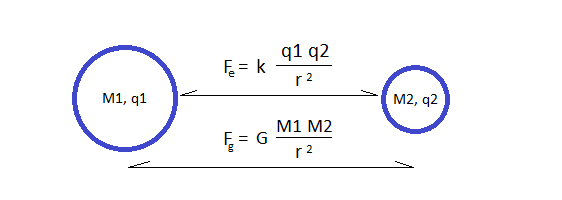

My position when it comes to the stability of orbits is that the role of static electricity is underappreciated by astronomers.

|

| Gravitational attraction and electrostatic repulsion |

The two bodies involved in an orbit are both negatively charged. My thinking is therefore that the impact on the smaller body should've been partially countered by the force of electrostatic repulsion. The combination of gravity and the electrostatic force should've mitigated the impact of NASA's probe in much the same way that a shock absorber overcomes mechanical shocks to cars.

Ejected fragments

But if a large number of fragments are ejected from the impacted object, much of that object's initial charge is lost. This is because charge resides mostly at the surface. The shock absorber is damaged, as it were. Much of the repelling force that existed in Dimorphos before the impact was taken over by fragments.

The fragments, highly charged as they were, got in this way an extra boost. Once released from the surface of Dimorphos, they accelerated away from Dimorphos and Didymos with more energy than predicted by NASA.

The net result of this was that NASA got the smaller orbit that it predicted, but also the more energetic fragments than it predicted.

My prediction, on the other hand, failed because the fragments took away the shock absorber effect that I had expected to see.

Had Dimorphos remained intact, with little to no debris ejected, my prediction may well have come true.

Jupiter's Children

An interesting aspect of this is that the ejection of debris from Dimorphos is similar in form to the theory that Jupiter ejects moons whenever it is sufficiently stressed to do so.

|

| Jupiter ejecting a moon |

The idea is that Jupiter will eject a moon every now and again, and that this happens with the assistance of electrostatic repulsion.

Once a blob of matter is pushed sufficiently high up, electrostatic repulsion kicks in, and the blob is thrown into space.

This explains the large number of moons orbiting large planets like Jupiter and Saturn. It may even explain Venus' odd behavior and apparent recent arrival in our solar system.

Objects thrown into space by parent objects gain extra energy from electrostatic repulsion.

However, this doesn't explain Dimorphos composition, which is different from what I had expected.

Bundle of rubble

As it turned out, Dimorphos was not the solid rock that I thought it would be. It was a bundle of rubble instead, which begs the questions. How was this assembled? Which force pulled it all together?

My position is that gravity is too weak to pull dust and rubble into lumpy asteroids. I'm not a big fan of the accretion disc theory. But the composition of Dimorphos seems to confirm this model. It can be argued that Dimorphos is the result of millions of years of steady growth due to gravity.

However, we can equally argue that the process of assembly is driven by static charge. Neutral bodies are attracted by charged bodies. Dust sticks to charged balloons. The phenomenon is well known. It's also a lot stronger than gravity.

Conclusion

The experiment performed on Dimorphos by NASA has taught us a lot about asteroids and orbits. But it has not provided conclusive evidence one way or another when it comes to the various theories related to this. All we can say is that the gravity only model is at a loss when it comes to explaining the extra energy evident in debris ejected by Dimorphos. Our competing mode, on the other hand, is only kept standing precisely because there was excess energy transferred to the debris.